The more we know, the less we think we know. Whether we’re learning Arabic, zoology, or cocktails, every lesson learned opens doors to a few others, and the world grows more vast and full of possibility.

Are you in an amaro, eau de vie, or absinthe phase? Obsessed with speakeasy culture, speed bartending, or mixing the perfect Negroni, without an end in sight? Wherever you’re at, there’s enough information available today - and more than enough products in today’s spirits market - to make just about any niche feel like the deepest and most infinite of them all, the one true thing.

In this six-part series, we’re making the case for each of the six major spirit categories as the most diverse in all of booze. This month, we’ve got a layup with everyone’s favorite spirit, whiskey. American, Australian, Canadian, Finnish, French, German, Indian, Irish, Japanese, Scottish, Swedish, and Taiwanese drinkers are already sold on it, but let's take a deep look to see what diversity is there.

HOW WHISKEY IS MADE

You can start whiskey from any grain. Whether you choose wheat, rye, corn, or another, it’ll need to malt, or wet and germinate, to break its complex starches into simple sugar. To get those sugars out where yeast can eat them, you’ll want to mash the the grain, grinding and further soaking it into a kind of porridge, properly known as the mash (noun). You could choose to strain out the solids, in which case the liquid is known as the wort.

Once you’ve got the mash or wort in your still, yeast can turn the sugar to ethanol, and as with any other distillation, the low boiling point of alcohol will produce a concentrated steam. Not too concentrated, since you want to keep the essence of your grain prominent, so you’ll be distilling to a less extreme proof than you would vodka.

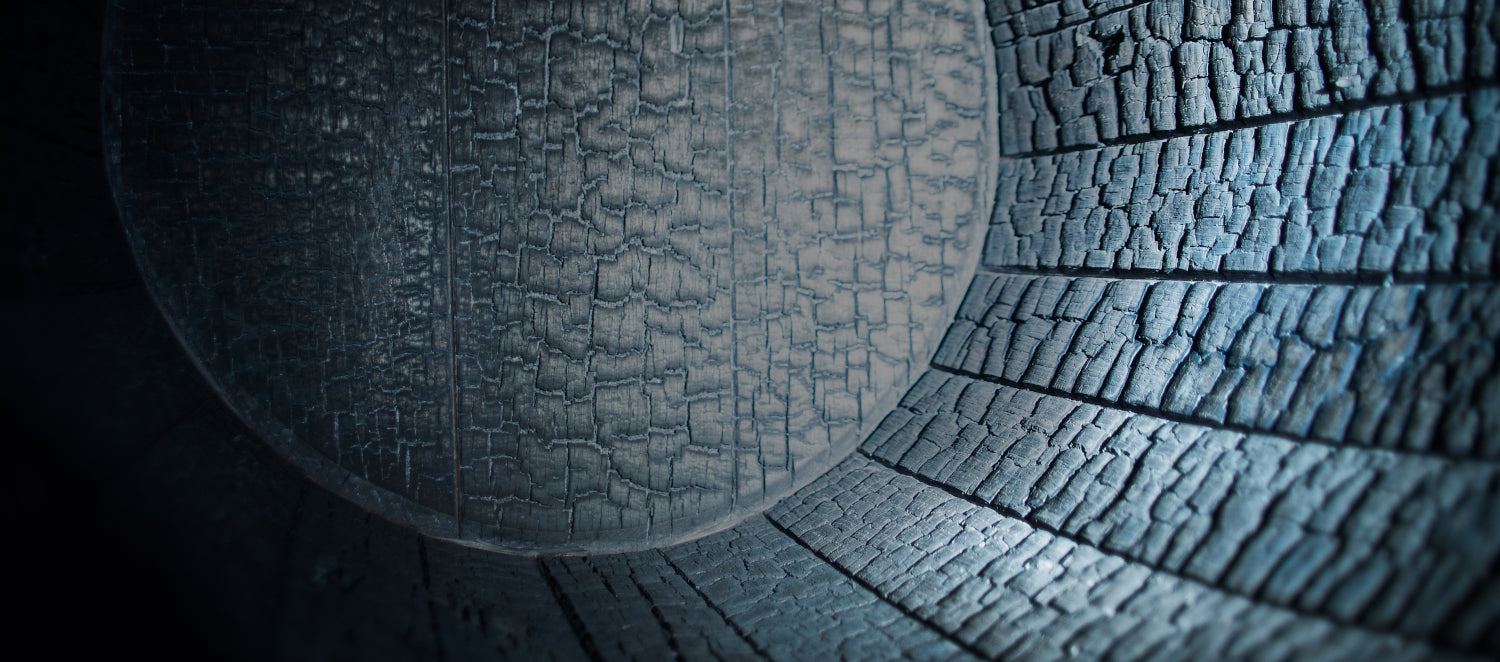

If you leave it at that, you’ve got white whiskey (Reddit's take on white whiskey), or white dog, but to make what most folks like to drink, you’ll want to rest it in wood barrels. Here you have further choices: what species of wood? What size of barrel, the bigger the less contact with the whiskey? Then there’s deciding how old a barrel, the more spent oak imparting less flavor. Plus, especially important for American whiskey, whether and how much to char, or toast, the interior of the barrel.

WHISKEY: THE INTERNATIONAL SPIRIT

Whiskey mashes are nearly always made from commodity grain, and aside from variations of origin, barrel size, and char, oak is oak. How then, with these two key factors narrowed, is the world of whiskey so diverse?

It's that these simple parameters make whiskey global, and therefore more available to different cultures and palates who put their own spin on it. It’s why Japanese whiskey and Kentucky bourbon can have so much in common at the molecular level and taste so different. Or why within the short boundaries of Ireland and Scotland both there’s such a wide variation of aroma and taste.

WHISKEY: GRAIN ELEVATOR

When you sidle up to a good whiskey bar and see several unfamiliar bottles, you only need be told the mash bill to get a good sense of your options. The breakdown of wheat, corn, and rye and barley malt in the mash gives you a well-educated guess at how the spirit will taste. Whiskey is perhaps the only spirit that works this way, that represents its ingredients so transparently.

Although some corn vodkas taste vaguely sweet and some rye vodkas feel spicy, vodka’s high-proof production method tends to obscure and homogenize the mash. Gin’s mash gets heavily masked by its botanicals, the recipes and distributions of which are too long and complex to provide immediate insight to aroma and flavor.

Knowing whether a rum is made from molasses, fresh sugar cane, or a combination only tells you a little, since fermentation and aging carry so much weight. Brandy gets close, since grape brandy, apple brandy, and the various fruit brandies communicate clearly to the palate, but we'll save the secrets of brandy for another post!

Agave spirits are the most deceiving of all: tequilas from highland and lowland Jalisco agaves are notoriously difficult to pick apart in blind tastings, and all the wild agaves whose piñas find their way under the tahona for mezcal can translate to radically different profiles depending on where they’re grown and the quality of the distiller.

But whiskey, made from consistent commodity products, stays true to them, making the mash bill a vessel of nearly endless flavor and texture settings.

Whiskey cocktail recipes make delicious use of this transparency. The julep and its variations, from the spicy King Smash to the rich and dark Coffee Julep, take full advantage of corn-based and gently sweet bourbon’s natural affinity for mint. The penetrating spice and texture of rye shines through or balances potent red vermouths in all kinds of Manhattans, absinthe in the Matchmaker and The Devil Inside, sweet and high-toned fruits in the Blinker #1 and The Right Stuff, and even balsamic vinegar in Fig Jam. The potent, complex barley malts of Scotch keep decadent, deeply-flavored cocktails like Midnight Matinee and Tiger stiff and strong.

Of course, whiskey drinkers aren’t mere white dog connoisseurs. It’s the synergy of mash, barrel, and time that give whiskey its infinite variations, applications, and places of prominence on top shelves and in liquor cabinets the world over.

WHISKEY: GRAIN ALCHEMIST

There are at least 500 species of oak, with about 90 in the United States alone. When coopered into barrels, these many woods can be sized, tightened, and treated (dried, toasted, and charred) in all kinds of different ways.

Cooperage goes back at least four and a half millennia to ancient Egypt, and the rollable oak beverage barrel as we know it dates at least to the Celts around 350 BC. It is not, then, a new technology. Its seen ages of advancements, adaptations, styles, and trends, all of which modern coopers and distillers can plumb for inspiration and innovation. More often, styles of whiskey have settled into specific combinations of these variables: a certain kind of oak, a certain size and condition of barrel, a certain method of cellaring.

Why should all that history be cast in favor of whiskey above all else? After all, there's no class of spirits that eschews oak altogether. That includes a few classic gins, and lately, even vodka. As anyone who’s lingered over an excellent extra añejo tequila or fine old rum, or contemplated the rancio in well-made Cognac can attest, oak and time are egalitarians.

The difference is that oak takes whiskey further than any other spirit. Those white dog connoisseurs aside, clear young whiskey has less in common with its final form than any other spirit. “White” rums and tequilas are delicious on their own, and are apparent in their aged versions. Even unaged Cognac, a clear distillation of wine, has some of the same flavors and unmistakable vinousness it’ll retain after 20 years in barrel.

Great whiskey becomes something else altogether. Married in the barrel, it hits the palate with power that can’t be traced back solely to either oak or distillate. It’s redolent of aromas uncharacteristic of wood or grain individually. It deserves time and contemplation, but not the kind where one scrutinizes it for its resemblance to its pre-barrel state a la aged agave spirits and rums. It's worth noting that agave spirits and rum conjure vigorous debate over whether the unaged spirit is superior, whether the oak just gets in the way, and if the distiller shouldn't have bothered with it in the first place. No such thing is said about whiskey.

GRAIN FUTURES

Despite its rich history, global popularity, and the dedication it attracts from its consumers and producers, there are vast bogs, bays, and plateaus of uncharted territory in whiskey. Small distilleries have begun, with varying success, to mash specific subspecies of grain and distill an entirely terroir-driven product. Once these approaches arrive on the competence and heritage we know from Scotland, Osaka, and Kentucky, watch out.

We may know, for example, that barley malt produces a whiskey as complex and interesting as any, but there’s enough unknown about the malt itself, let alone which ones ought correspond to which oaks and aging processes, to conceal a hundred possible great whiskeys. There’s a reason Brew Cabin adds a “So Far” to their malt guide: there’s a lot of innovation yet to take place.

Smart chefs and bakers of the past decade have become much more intentional when choosing grains and flours. The American consumer is growing more likely to have favorite varieties, and more used to the idea of a menu or recipe calling for a particular strain of wheat, rye, or corn for bread, pasta, or tortillas.

Even the best-crafted of those don't take quite as much time to make as whiskey, let alone great whiskey, but devotees are dedicated and undaunted by time. It won't be too far behind.

Interested in the rest of this ongoing six-part series on spirits? Check out our other articles on how gin and vodka are made.